A report on our August 17 workshop at BioMarin San Rafael

Opening meditation by Maeve Murphy

Moderator: Stuart Moody

Panelists:

Maureen Parton, Marin County Supervisor’s Aide

Maureen Parton, Marin County Supervisor’s Aide- Renee Goddard, council member, Town of Fairfax

- Ella Ledyard, Ross Valley School District alumna

- Mary Kay Sweeney, Executive Director, Homeward Bound

- Andy Peri, former advocacy director, Marin County Bicycle Coalition

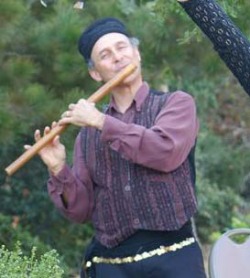

Closing flute rhapsody by Michael Davis, US Pure Water

Like many counties across the state, Marin County is facing challenges that won’t go away easily. Some may be unique to our area, but others are common to many municipalities. Homelessness, traffic congestion, climate change, and the relentless pressure of rising populations all need our attention. And they need faster response than we have given them in the past.

How do we get traction on issues when emotional temperatures rise? How do we create solutions that serve the greater good and build community instead of dividing it? These are the questions we pondered together on August 17.

Andy Peri gave one answer, in his story of facing Hal Brown’s anger over the Marin County Bicycle Coalition’s “taking” of a 150-foot strip of roadway. The strip had been much-used by local parents for parking and drop-off at Kent Middle School along College Avenue and was now designated for a bike pathway. “Listen for the needs,” Andy said. “If you can identify the needs, then you can generate solutions. Dichotomies are never true, and they’re guaranteed to create conflict.”

“How do you get beyond dichotomies?” Peter Graumann and Greg Brockbank asked this question for many of us. So many issues that come before decision-makers are constructed as dichotomies: do you approve the project, or do you deny it? Do you vote for the proposal, or against it?

Additional answers appeared in many forms through the evening. Here is a summary of thoughts from the other panelists, followed by principles and practices embedded in their presentations and in the larger conversation.

Maureen Parton. “What seems like a blessing may be a curse. What seems like a curse may be a blessing.” Her example: Charles McGlashan’s recovery from unexpected opposition by local grocers to his proposed ban on plastic tote-bags. Going back to the drawing board, Charles and team (including Maureen) built a coalition of advocates, grocers, and county officials. Over a series of meetings, this group came up with a plan that was better than what Charles had initially proposed. The ban passed at the Board of Supervisors without any local opposition. Photo: Charles Mc Glashan & Susan Adams interviewed by KCBS.

Maureen Parton. “What seems like a blessing may be a curse. What seems like a curse may be a blessing.” Her example: Charles McGlashan’s recovery from unexpected opposition by local grocers to his proposed ban on plastic tote-bags. Going back to the drawing board, Charles and team (including Maureen) built a coalition of advocates, grocers, and county officials. Over a series of meetings, this group came up with a plan that was better than what Charles had initially proposed. The ban passed at the Board of Supervisors without any local opposition. Photo: Charles Mc Glashan & Susan Adams interviewed by KCBS.

Renee Goddard. A metaphor for our public conversations: what if we were to see community projects and issues as nature treks – shared journeys where cooperation is essential, where participants extend helping hands whenever needed to ensure that each member of the group is safe and successful, and where beauty and wonder are all around?

Many “C” words express the soul of civility: compassion, concession, conversation, constructiveness. Another key word: crisis. Crises in public policy can become opportunities for growth when we see them through the lens of the cooperative nature trek. Differences in opinions, then, cam drive solution-making, as each participant has the potential to bring at least one new idea, skill, or piece of information to the process.

Ella Ledyard. Anonymity can degrade civility. This is the danger of social media: it’s easier to say things without thinking through the possible effect on their readers. Level-headed discussion takes more time, but it can prevent hurt feelings. The ease of typing out one’s thoughts and opinions makes it all the more important to take a step back and look at what you’re saying before you send it. Be conscious of what you are saying!

Mary Kay Sweeney. Example of civil discourse at work: the Dominican Sisters’ “Yellow Hallway” project. The Sisters followed a stepwise procedure:

- Hosting a reception for neighbors in a quiet, comfortable, holy setting. Sitting in a circle with wine and cheese, Sister Maureen described the plan. The sisters calmly listened to all the concerns raised by the neighbors.

- Meeting with City officials to review zoning concerns and how to apply for an easement.

- Speaking before the Planning Commission

- Speaking before the City Council

Three elements of their approach:

- The sisters were clear on the goal, and stayed focused on their motivation: “We have space, and we want to share it.”

- Proponents spoke calmly, knowledgably, and eloquently.

- They showed how the project was part of the solution to a larger problem that the whole community acknowledges.

Photo: volunteers at Homeward Bound’s New Beginnings Center, Hamilton Parkway, Novato:

Anna Pletcher, attorney, complemented these ideas with a reminder of the power of story. Recounting an experience or series of events, when done authentically and with good will, can stimulate imagination and draw people into exploring ideas with you.

Sashi McEntee, Mill Valley city council, pointed out that when citizens come to council meetings and other public hearings, it is usually because they have a complaint or a concern. They are also giving up something else that they would rather have been doing, such as having dinner with their family or taking care of their home. They are thus likely in a state of discomfort or tension. Recognizing the inconvenience, if not discomfort or suffering, inherent in this situation can help public officials remember to stay compassionate and considerate.

More principles & practices

Vision. Begin with a plan. Define clearly the outcome you hope for. Keep the goal in mind.

Prepare. Do your homework. Get to know the issue as thoroughly as you can, so that you can present your ideas clearly, and be receptive to others’ input.

Outreach. Concentrate on friend-raising. The underlying agenda for every issue campaign or project is building community.

Listen. Take time to listen, so that you may truly understand each other. Be open to learning from those whom you came to persuade. They may persuade you as well.

Empathy. Think of the other side. They have needs and goals, too. Listen for these needs, acknowledge them, and talk together about how these needs can be fulfilled at the same time that yours are being addressed.

Respect. Remember that each person is to him or herself the most important person in the world. Remember that everyone is trying to avoid suffering and to find satisfaction.

Flexibility. In the light of what you learn from others, explore what kinds of adjustments might improve your original plan.

Patience. Give your project time to take shape and ripen.

Calm. A modicum of inner peace helps with all of these elements above. A clear and tranquil mind can think more effectively, listen more easily, and see more deeply our shared humanity.

Calm. A modicum of inner peace helps with all of these elements above. A clear and tranquil mind can think more effectively, listen more easily, and see more deeply our shared humanity.

If you can do these things, the resulting compromise (i.e., the co-created solution) can bring more benefit than the plans that advocates, opponents, and/or decision-makers had originally brought to the table.

As Thich Nhat Hanh put it so simply, “We must be aware of the real problems of the world. Then, with mindfulness, we will know what to do and what not to do to be of help. If we maintain awareness of our breathing and continue to practice smiling, even in difficult situations, many people, animals, and plants will benefit from our way of doing things.”

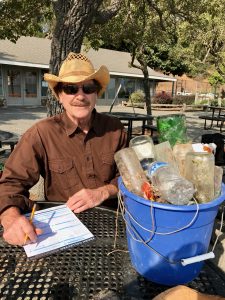

As Thich Nhat Hanh put it so simply, “We must be aware of the real problems of the world. Then, with mindfulness, we will know what to do and what not to do to be of help. If we maintain awareness of our breathing and continue to practice smiling, even in difficult situations, many people, animals, and plants will benefit from our way of doing things.” Soon we were joined by 14 enthusiastic volunteers of all ages who combed the beach and brought back bucket-loads of plastic, fishing line, bottles and all manner of discards – 29 pounds in all. The most charming item? A tiny plastic toy goose. The biggest/most unwieldy? A box spring mattress (we flagged that one for the rangers to collect later, exceeding the weight of everything else we collected). Volunteer Hailey came back again this year with her Girl Scout pals to celebrate her 11th birthday – she celebrated her 10th here last year, too.

Soon we were joined by 14 enthusiastic volunteers of all ages who combed the beach and brought back bucket-loads of plastic, fishing line, bottles and all manner of discards – 29 pounds in all. The most charming item? A tiny plastic toy goose. The biggest/most unwieldy? A box spring mattress (we flagged that one for the rangers to collect later, exceeding the weight of everything else we collected). Volunteer Hailey came back again this year with her Girl Scout pals to celebrate her 11th birthday – she celebrated her 10th here last year, too.